Progress towards achieving 2020 export targets

4 March 2020

2020: The year of soil biology and integrated weed management

5 March 2020Brown etch, or rust mark, is a major issue for butternut pumpkin growers. A project recently completed by Applied Horticultural Research examined the causes of this disorder and what can be done to reduce the risk of it occurring in the field or after harvest. Dr Jenny Ekman provides a summary of outcomes from this strategic levy investment.

Growers of butternut pumpkins are likely all too familiar with brown etch, or rust mark. Although eating quality is unaffected (the brown areas are purely superficial), the appearance of etch greatly reduces the value of the crop. In some cases, it may not even be worth harvesting.

Initially, brown etch develops in the field. It usually develops from a contact point with the soil, a stem or other pumpkins. Etch can appear as either a pattern of concentric brown rings, or as irregularly shaped brown blotches spreading across the fruit. Symptoms can also develop after harvest, so that a freshly packed, clean bin of pumpkins at the farm can be riddled with etch by the time it arrives at the wholesale markets.

Examination of pumpkin skin using scanning electron microscopy reveals massive thickening of the cell walls in etched areas of pumpkin skin. This is due to accumulation of lignin, a key compound in wood and bark that is also often produced to defend cells from physical stress or fungal attack. As a result of this thickening, the cell contents are squashed and disrupted. Eventually the cells die, leaving behind the whitened skeletons of their cell walls. Etch can be associated with infection by gummy stem blight or “black rot” (Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum). Immature pumpkins artificially infected with this disease often develop symptoms of etch. In this case, the pathogen can be re-isolated from the etched tissue.

However, etch also occurs when plants appear totally free of this disease, with no other symptoms of infection or evidence of fungi from RNA analysis or microscopic examination.

Rain and etch

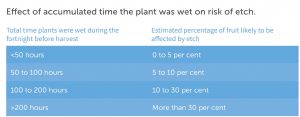

One thing that is certain is the correlation between etch and wet weather. Wet conditions due to rain or dew are strong predictors of the risk of etch in a crop. This is often cumulative. For example, the values shown in the table below are based on a model using the total accumulated time spent wet during fruit maturation. These are estimates only; rates of etch are also likely to vary due to other factors.

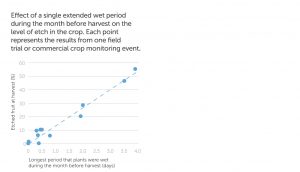

However, a single extended wet period can trigger increased rates of etch, even if the crop stays relatively dry before and after this event. The graph below is most useful as a guide to potential incidence after an extended rainy period. Therefore, etch seems most likely to be triggered by stress. Etch can be a response to infection by gummy stem blight, but also to exposure to wet conditions. If etch is observed in the field, then more is likely to develop during transport and storage. New blemishes can appear overnight on previously clean fruit, as well as continuing to expand on already affected fruit. While new or expanded etch mainly occurs during the first week of storage, it can continue to appear for up to two weeks.

Conversely, if there is little or no etch in the field, symptoms are extremely unlikely to develop after harvest. We tested a large range of different products and techniques to reduce etch, including fungicides, nutritional supplements and products reported to improve plant defences. None were effective. There also appeared to be little difference in susceptibility between common butternut varieties.

Project findings

It seems likely that the best way to reduce development of etch is to keep relative humidity (RH) low and the crop as dry as possible. This could mean increasing plant spacing, avoiding planting in damp areas or growing with subsurface drip instead of overhead irrigation. If etch is present in the field, it may be best to store harvested pumpkins for at least a week before re-packing into hat bins or crates. By this time development of new etch will be minimal, allowing effective grading of the remaining fruit.

Development of etch during transport and storage may be reduced by keeping RH very low and, potentially, by cooling fruit. While five degrees Celsius storage reduced etch development by more than 75 per cent, more suitable temperatures have yet to be tested using fruit at high risk of etch development.

The current drought means that etch, at least, won’t be a problem for pumpkin growers. However, rain will eventually fall again, raising the question of what to do with etched fruit.

Most butternut pumpkins are sold cut in half and overwrapped – the undamaged flesh is clearly displayed, despite the brown stain on the skin. We conducted a small retail study looking at consumer preferences. Header cards were included showing etched and non-etched fruit, trying to clarify the difference between the two groups for consumers.

When we discounted etched fruit by 50 cents per kilo, we sold 12 per cent more etched than clean pumpkins. Even without a discount, etched pumpkins still sold well. This suggests that if people can see the flesh is good to eat, purchasing will be minimally affected.

Perhaps simply cutting etched fruit in half could solve what is, after all, a problem that is only skin deep!

Find out more

For a fact sheet on brown etch of pumpkins, or for more information on this project, please contact Dr Jenny Ekman.

Improved management of pumpkin brown etch is a strategic levy investment under the Hort Innovation Vegetable Fund. This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable research and development levy and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: VG15064

Etched pumpkin, showing a typical pattern of concentric rings. In the centre the cells have died, leaving behind the white skeletons of their cell walls. Black fungal spores can be seen in the dead tissue.