Bridging borders: AUSVEG Reverse Trade Mission showcases Australia’s horticultural strength

2 September 2025

The Skye’s the limit for smart nutrient management

3 September 2025BY DR JOHN STANLEY, RAMESH PURI AND DR HEIDI PARKES,

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, QUEENSLAND

Figure 1: Typical setup of emergence cages positioned over maize plants, one month after initial fall armyworm infestations at DPI Bowen, QLD, October 2024.

Area-wide management (AWM) of the invasive fall armyworm aims to reduce overall pest pressure by limiting survival from one generation to the next across a whole region. Through a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach, we worked with growers and agronomists in the Bowen–Burdekin region on the practical question: do standard weed cultivation practices help reduce the survival of fall armyworm in sweet corn?

Fall armyworm goes to the ground to pupate for one to two weeks before emerging as a moth and reinfesting sweet corn, maize and sorghum crops. Our trials explored whether standard interrow weed cultivation targets and disrupts the pest at this vulnerable stage. We also looked at the effect of a shallow soil disturbance that simulated robotic weeding. A major goal was to include grower-led observation and feedback through field visits and collaborative planning, an approach known as participatory action research or PAR (Figure 1 and 2).

Our trials explored whether standard interrow weed cultivation targets and disrupts the pest at this vulnerable stage.

Our trials explored whether standard interrow weed cultivation targets and disrupts the pest at this vulnerable stage.

Weeding out fall armyworm in sweet corn

Figure 2: Dr John Stanley discusses a fall armyworm management trial with agronomist John Nancarrow from Vee Jay’s Kalfresh.

Our results showed that sweet corn growers can expect that their interrow weed cultivations will seriously disrupt fall armyworm emergence. We found as much as an 80 percent reduction in moth emergence following typical weed cultivations (along the side of each corn row with ~10cm wide scarifying tips down to 10cm).

Cultivation often occurs three to four weeks after crop emergence, at about the same time that early infestations of fall armyworm are going to ground to pupate. Those pupae are typically within 20cm of the plant row and down to about 7cm in our sandy clay loam soils (Figure 3). Most are close to the plant line and within the top 4cm.

Uncultivated rows (control) were compared to cultivated rows by collecting emerging moths in large mesh cages (50cm wide x 80cm long, see photo). Every day, we counted and collected moths and parasites (flies and wasps) that emerged into the cages (Figure 4).

How it works

We believe that cultivation directly damages the pupae and/or simply collapses the tunnels the insects rely on to get back to the surface. Heaping of the soil against the base of the plants during cultivation probably also plays a part in burying emergence holes between plants within the row where the plough tine does not directly cut through. This pupae busting is an aspect of area-wide management that aims to reduce the overall pest pressure of future populations.

Potential robotic pupae busting

Figure 4: A cage set up in a sweet corn trial to capture emerging fall armyworm moths at DPI Bowen, Queensland, in October 2024.

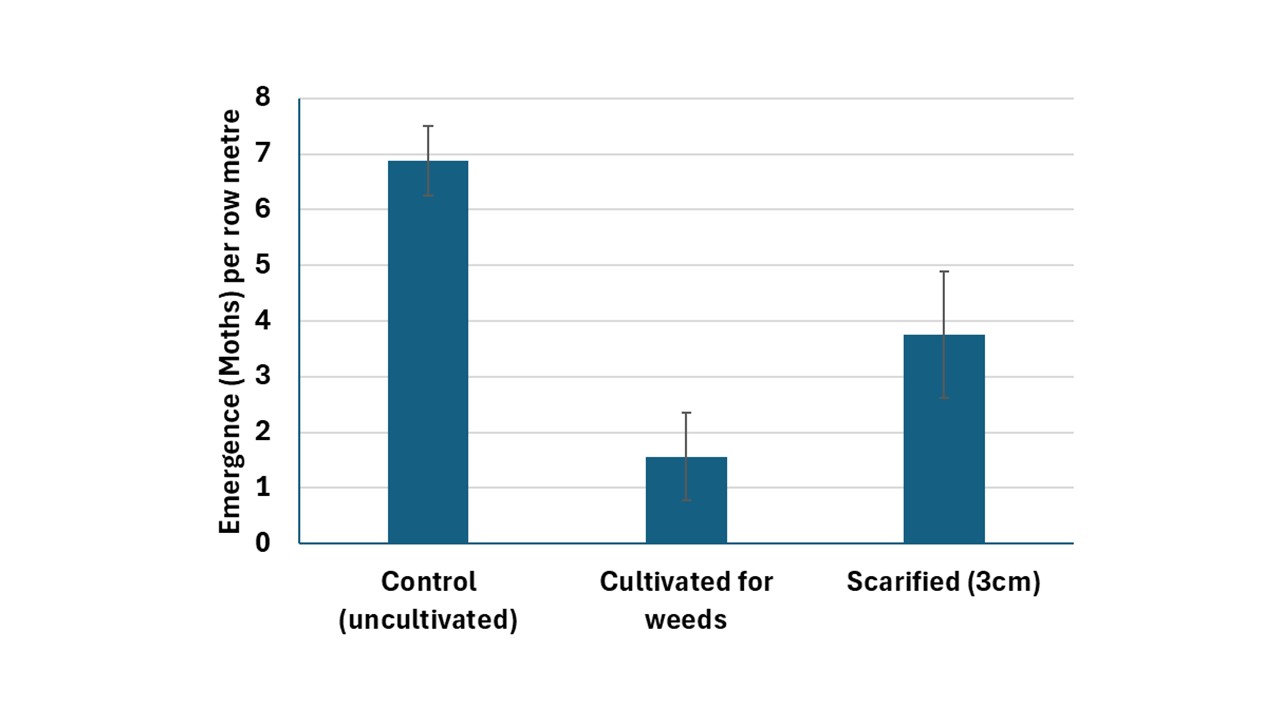

For another set of cages, we manually scarified the soil to a depth of 3cm, to see whether the action of a robotic weeder might disrupt fall armyworm emergence tunnels well enough to cause pupae busting. This appeared to cause 40 percent mortality, about half the mortality caused by the typical tractor driven cultivation (Figure 5).

Very high levels of parasitism in unsprayed maize

In similar trials, an estimated 90 percent parasitism of fall armyworm occurred. This shows that many of the parasites that attack our native pests, like Helicoverpa and Spodoptera litura, are adopting the fall armyworm (invader) as a host.

Figure 5: Emergence of fall armyworm per row/metre of maize following cultivation for weed control using spear points to 10cm along, or surface scarification to 3cm across the entire soil surface around plant stems. Error bars are StdErr (n=4)

Take-home message

Pupae busting occurs while sweet corn growers carry out their usual weed cultivations. Also, later generations of fall armyworm are becoming heavily parasitised as late instar larvae or pupae in unsprayed crops, typical of rain-grown sorghum and maize crops. Weed control cultivations do not usually occur later in the sweet corn cropping cycle because these crops get too tall and weeds are shaded out.

So, the final opportunity for pupae busting would be immediately after harvest. Fall armyworm pupae do not diapause (do not ‘hibernate’ to overwinter) so cultivation, as early as possible after harvest, has the benefit of pupae busting fall armyworm that might have been selected for insecticide resistance.

MORE INFORMATION

Visit QDPI’s FAW Engagement Hub at dpi.engagementhub.com.au/fallarmyworm