Veggies in-focus for Victorian schoolchildren

3 March 2020

Assessing the economic impact of weeds in Australian vegetable production

3 March 2020In 2017, a Hort Innovation Vegetable Fund project was established to recognise the damaging impact that vegetable leafminer could have on some of Australia’s fresh produce industries if it were to move into production regions. AUSVEG Biosecurity Officer Madeleine Quirk explores the role of parasitoid wasps in controlling vegetable leafminer populations in far-north Queensland, the importance of parasitoid wasps overseas, and research conducted into reservoirs of parasitoid wasps within Australia’s non-pest leafminers.

Vegetable leafminer (Liriomyza sativae; VLM), potato leafminer (Liriomyza huidobrensis) and American serpentine leafminer (Liriomyza trifolli) are exotic flies that cause significant damage to horticultural commodities overseas, and potentially threaten Australia’s vegetable, nursery, melon and potato industries.

VLM established itself in the Torres Strait in 2008 and was subsequently found on mainland Australia, in Seisia on the Cape York Peninsula, in 2015. However, VLM populations have not reached problematic levels – instead, they seem to be held in check largely by tiny biological control agents called parasitoid wasps.

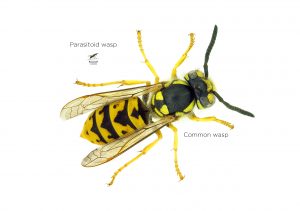

What is a parasitoid wasp?

Parasitoid wasps that attack leafminer flies are less than two millimetres long. Female wasps lay their eggs on or inside fly larvae or pupae, and when the eggs hatch, the wasp larva eats the fly larva/ pupa before completing its development and emerging as a new adult wasp. Some of the adult wasp species also kill large numbers of leafminer larvae by directly feeding on host larvae to acquire nutrients for the development of additional eggs in the wasp.

Dr Peter Ridland from the University of Melbourne has conducted a literature review of the wasps that parasitise leafminer flies in Australia and internationally.

“Those native and invasive leafminer species studied in Australia have a large range of parasitoid wasp species attacking them. Some of these wasps are also exotic and presumably arrived in Australia many years ago with their host leafmining flies,” Dr Ridland said.

“Australia has at least 50 species of parasitoid wasps known to parasitise native leafminer flies. Many of these species are known to attack vegetable leafminer overseas, including Hemiptarsenus varicornis and Diglyphus isaea. The good news is that Australia will not need to import any new parasitoid species for the biological control of vegetable leafminer.”

News from the incursion front

Cesar Research Scientist Dr Elia Pirtle has undertaken extensive field research in the Torres Strait and Cape York Peninsula, studying parasitoid wasps and their relationship with VLM.

“Some of our Australian species already show signs of very effective vegetable leafminer control on the incursion front in far-north Queensland. We have found at least six species of parasitoids attacking vegetable leafminer and, in some cases, unassisted field rates of parasitism can reach as high as 80 per cent,” Dr Pirtle said.

“While there may be a lot of factors contributing to vegetable leafminer’s limited mainland distribution, we predict that it is, in part, due to these wasp populations slowing down its spread.”

Chemical use: a global problem

Although the tiny parasitoid wasps are keeping leafminer numbers low in far-north Queensland, they are extremely sensitive to chemicals and can be wiped out by a single spray. When a crop is sprayed, beneficial insects such as predators and parasitoid wasps are knocked out while VLM, sheltering in the soil as pupae or as larvae in mines, continue to breed and multiply.

This is referred to as a secondary pest outbreak, meaning that it is not until its natural enemies are destroyed that the surviving leafminers become a problem for growers. That is especially true when they start to develop resistance to common insecticides, even if the insecticides are targeted at other pests in the crop.

“Overseas, excessive use of nonselective insecticides has caused devastating leafminer outbreaks for growers,” Dr Ridland said.

“On the other hand, it has been demonstrated repeatedly that conservation of parasitoids is one of the foundations of a successful integrated pest management system.

“While we can’t say for sure how parasitoids might affect vegetable leafminer populations in Australian production regions in the future, we are confident that this approach will underpin its successful management.”

Examining relationships

Marianne Coquilleau is a Master of Philosophy Candidate at the University of Melbourne. For two years, she has been sampling mined plants and rearing specimens from six sites around Melbourne to examine the effect parasitoid communities have on several local leafminer fly species.

“The four common leafminers are Liriomyza brassicae, Liriomyza chenopodii, Phytomyza plantaginis, and Phytomyza syngenesiae,” Ms Coquilleau said.

In Victoria alone, Ms Coquilleau found that those four flies that feed mostly on weeds are attracting and maintaining a healthy community of nine genera of parasitoid wasps.

“Though this number may seem low, it’s a good start for focusing on species and populations already established and suited to the Australian climate,” she said.

Parasitoid wasps are not fussy when it comes to their diet and tend to overlap with each other in their favourite leafminer to eat. In fact, L. brassicae was found to be parasitised by every wasp species that our project team found around Victoria. This supports Dr Pirtle’s findings from Seisia: there are a wide range of local biocontrol agents that could be utilised for vegetable leafminer control, and it is likely that more wasp species will develop a taste for VLM if it spreads.

“We are banking on that being the case for the local parasitoids to shift onto invasive exotic leafminer species,” Ms Coquilleau said.

Some of the parasitoid wasps found in Victoria are distributed across the Torres Strait and Cape York Peninsula, and already appear to be attacking VLM in the north. These include Zagrammosoma latilineatum and Hemiptarsenus varicornis.

“More research needs to be done to look at parasitism levels over time, and across different wasp species combinations. These detailed studies cannot be undertaken until vegetable leafminer invades the Australian production regions, which we hope is delayed for a long time,” Ms Coquilleau said.

Overall, Ms Coquilleau’s research reinforces that local Australian parasitoids will be the cornerstone of future integrated pest management strategies, and we already have several species to choose from. She also hopes that it is a first step towards looking at the temporal presence of wasps of interest and their non-pest hosts, so that it can be taken into consideration when it comes to spraying schedules.

What we do know for certain is that if vegetable leafminer spreads to agricultural regions, it will become essential for growers to protect and promote their parasitoid wasp communities and integrate them into their pest management regimes.

Subscribe for leafminer project updates

Be sure to keep up-to-date on VLM project updates and upcoming workshops by subscribing to the AUSVEG Front Line e-Bulletin. To subscribe, click here.

Find out more

For more information, contact AUSVEG Biosecurity Officer Madeleine Quirk on 03 9882 0277 or email madeleine.quirk@ausveg.com.au. Alternatively, you can visit the project page on the AUSVEG website.

Any unusual plant pest should be reported immediately to the relevant state or territory agriculture agency through the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline (1800 084 881).

The Research, Development and Extension program for control, eradication and preparednesss of vegetable leafminer has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable, nursery, melon, and potato research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: MT16004