Potato growers continue to trade through COVID

24 March 2021

Growers urged to test to minimise soil-borne disease risk

25 March 2021Pink rot is a soil-borne disease caused by the pathogen Phytopthora erythroseptica. A factsheet – produced by RM Consulting Group – provides information on the pathogen, its lifecycle and management options.

Management options

Use the following options to help manage pink rot:

- Use Metalaxyl and Metalaxyl-M (mefenoxam)* according to label instructions.

- Keep soil moist (between field capacity and above wilting point) but without excess moisture.

- Use the PreDicta Pt service to identify areas that are infected with the pink rot pathogen.

- Avoid planting into soils that are compacted (> 2000 kPa with a penetrometer) and/or waterlogged. Consider using controlled traffic and/or minimum tillage practices to improve soil condition.

- Remove all volunteers and weeds that can act as potential hosts.

- Avoid mixing tubers from contaminated areas with other tubers during storage or better still avoid harvest of contaminated tubers.

- Rotate potatoes with other crops (for at least four years).

- Use clean, certified seed.

* Note: Metalaxyl is effective in Australia but resistance has been identified in the US where the active ingredient has been overused in the crop rotation. Metalaxyl is a chemical which has been shown in certain soils to develop enhanced biodegradation (i.e. the soil microorganisms use it as a food source and thus it is rapidly degraded before it can be effective). This is more likely to occur with repeated usage on many crops.

Potential management options

Research has shown that:

- Biofumigants such as mustards can be effective. Biofumigants should be used according to best practice advice.

- Low soil pH (<5) in the rootzone and low levels of free calcium in the soil solution may increase pink rot severity. Liming and soil application of soluble calcium fertilisers may alleviate this risk (by increasing the pH and the soluble calcium). Further research is required to better understand this relationship.

The pathogen and disease

Pink rot of potato is an important soil-borne storage disease of potatoes worldwide. It is caused by the fungus Phytophthora erythroseptica and sometimes by Phytophthora cryptogea. Pink rot infection is often associated with secondary infection by anaerobic soft rot bacteria.

Key features of pink rot are that:

- Infections vary in virulence.

- Some cultivars are less susceptible than others but can still get the disease to some extent.

- It can survive for long periods in the soil (up to seven years).

- It can be spread by tubers, water and soil.

- It develops rapidly at soil temperatures from 10 to 30°C with 25°C optimal for infection.

- It resembles blackleg in early infection stages.

- There are many plants that act as hosts, including many weed species.

- High humidity along with poor ventilation can cause heavy losses of stored potatoes.

Diseased plants are first observed in poorly drained (waterlogged) parts of the field and late in the season, near harvest. Disease symptoms are mostly characterised by stunting and wilting of plants.

Wilting starts from the base of the stem and progresses upward, causing leaf yellowing, drying and defoliation. Vascular discoloration and blackening of the underground stems may also be observed.

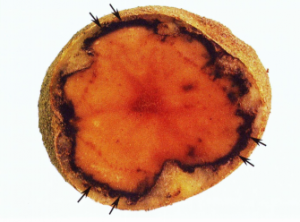

Similarly, roots may turn brown to black, and occasionally aerial tubers may develop. Symptoms on tubers are more obvious and characteristic of the disease. Tuber decay begins at or near the stem or stolon end of the tuber. Infected tissue becomes rubbery but not discoloured in the early stages of infection, and when infected tubers are cut open the rotted portion is bordered by a dark line visible through the tuber skin (see Figure 1). The tuber skin (periderm) over the rotted portion is light brown in white-skinned cultivars.

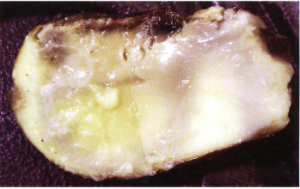

Pink rot is not a slimy soft rot, and rotten tissues remain intact but spongy. When rotten tubers are cut open, the internal tissues are cream-colored and usually odourless. The tough, leathery, rubber-like texture of infected tubers distinguishes pink rot from bacterial rot disease where the diseased tissue becomes soft and pulpy and contains numerous cavities.

However, infected tissues are easily invaded by secondary pathogens, such as soft rot bacteria (Pectobacterium spp.), which produce the slimy symptoms often found in potatoes with pink rot (see Figure 2).

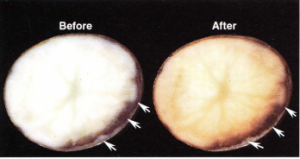

As tubers are exposed to the air, the colour of the infected tissue progressively changes from cream to salmon pink within 15 to 30 minutes (see Figure 3). After about one hour, the tissue gradually turns brown and then black. If the cut tuber is squeezed, a clear liquid may ooze out of the cut surface.

Figure 3: Tubers infected with pink rot turn pink after exposure to air for 15 to 30 minutes. Arrows indicate diseased tissue.

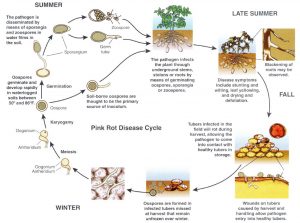

Disease cycle

The disease cycle of pink rot is shown in Figure 4 (see below). The pathogen can be transferred by:

Soil – to new fields via farm machinery and bins, and within an infested field during cultivation.

Tuber – the surface of healthy tubers may be contaminated with oospores from infected tubers that were missed during harvest (volunteer potatoes) or in cull piles that will end up in the soil after deterioration of the tubers.

Water – irrigation water is also an important source of movement of the oospores from one location to another within a field and among nearby fields.

Further research

The following pink rot research reports can be found by searching the project numbers on the InfoVeg webpage.

Pink rot in potatoes. Image courtesy of Michael Rettke from the South Australian Research and Development Institute.

- PT97026 – Developing soil and water management systems for potato production on sandy soils in Australia

- PT97004 – Potato pink rot control in field and storage

- PT01042 – Potato pink rot control in the south east of South Australia

A previous article entitled ‘Controlling pink rot in Australian potatoes’ appeared in Potatoes Australia – June/July 2017. The article can be found on page 31 in this magazine.

Find out more

Please click here to read the full factsheet, including links to further reading and references.

This factsheet was produced under Program Approach for Pest and Disease Potato Industry Investments, a strategic levy investment under the Hort Innovation Fresh Potato and Potato Processing Funds.

This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the fresh potato and potato processing research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: PT17002

This article features in the autumn 2021 edition of Potatoes Australia. Click here to read the full publication.

Figure 4: The disease cycle of the pink rot pathogen, Phytophthora erythroseptica. Illustrations courtesy of Marlene Cameron.