Focus on food industry and vegetable-based product development

24 November 2021

Climate positive practices: Aussie veg producers acknowledged on the world stage

25 November 2021You’ve nailed single species cover crops use on your farm and are now considering the next step. If you jump on the web, mixed-species mixed cover crops are the buzz. Three-, eight- or even 30-species mixes are often promoted as the silver bullet for improving soil health and productivity. In this column, Kelvin Montagu from Applied Horticultural Research discusses when to stick with single species cover crops and when to jump into mixed species cover crops.

Are mixed species cover crops a good fit for vegetable production?

To answer the question, you need to be clear about your main aim and how long you have for the cover crop.

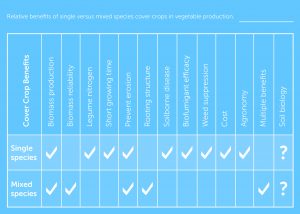

In the below table, I have summarised the relative benefits of single versus mixed cover crops in vegetable production. This is based on my experience and research reviews.

As you can see, I like to keep it simple with single species cover crops. If a single species cover crop delivers, stick with it. They are cheaper, easier to manage and often deliver more specific benefits.

If you are new to cover cropping, then definitely start with single species cover crops.

When single species cover crops are the winners

When managing soilborne disease pressure, carefully chosen single species cover crops are a clear winner.

Non-hosting cover crops, or break crops, are an important way of reducing soilborne disease pressure. Typically, cereals (e.g., oats, cereal rye, sorghum, millet) are used in the vegetable rotation as a break crop.

Moving to a mixed species cover crop greatly increases the likelihood that one of the additional species will be an alternate host to the soilborne disease. This complicates your rotation and can increase losses caused by soilborne disease in the following vegetable crop. Choose wisely.

The amount of biomass produced by cover crops is important for biofumigation efficacy, nitrogen fixation by legumes and suppressing weeds. Carefully chosen (right season and sowing rates), single species cover crops will usually produce more biomass than mixed species cover crops. For both nitrogen fixation and weed suppression, biomass is king.

Maximum biomass is particularly important for biofumigants that rely on high biomass and rapid incorporation into the soil for their efficacy. Adding in other species will reduce the biomass of the biofumigant and hence the biofumigation efficacy. See the biofumigation section below.

For guidance on single species cover crops, check out the Cover Crops for Australian Vegetable Grower Poster.

If single species cover crops are your choice but you want to introduce more diversity, consider changing your cover crop species occasionally to provide more diversity.

Single species cover crop – oat cover crop before corn in Richmond, New South Wales. Image courtesy of Kelvin Montagu.

Where do mixed species cover crops fit?

If you have long cover crop growing time and no soilborne disease issues, then mixed species cover crops can be a good option. The mixes can provide a greater variety of rooting structures to help build soil structure (e.g., including some ryegrass with cereal and adding in a deeper rooting brassica), or a wider range of flowering plants to help maintain beneficial insects. There is also evidence that nutrient cycling is more efficient in mixed-species system.

A longer growing time and different management practices (e.g., grazing or mowing) will be required to allow different species to contribute to mixed species cover crops. In general, the most successful mixed species cover crops have been in grazing systems – and then I would call them pastures!

There is also a lot of talk about mix species cover crops being better for soil biology – greater diversity in the cover crop creates greater diversity in soil biology is the logic. However, the research is not clear cut on mixed being better than single species cover crops. But what is clear, is that any cover crop is way better than a bare fallow.

If you want to try mixed species cover crops, then start building with one or two additional species and make sure the benefits you want are being delivered, and that you are not compromising or complicating your money-making vegetable crop.

Single species cover crop trial – millet oats, ryegrass and tillage radish before a baby leaf crop in southern Tasmania. Image courtesy of Kelvin Montagu.

Biofumigation: Keep it simple for maximum soilborne disease management

Recently, a grower rang me following a crop loss from Sclerotinia in lettuce. He had successfully used caliente biofumigant to reduce the Sclerotinia pressure prior to growing the lettuce.

With this working well, he thought a mix species cover crop might bring more benefits so added in a cereal and legume. However, he lost sight of the main aim of managing Sclerotinia levels.

By adding in more species, the effectiveness of the biofumigation cover crop was probably reduced. Firstly, the cereal and legume would have ‘diluted’ the biofumigant action by reducing the amount of biofumigant biomass produced. Maximum biomass incorporated at the right time is required for a biofumigant to be most effective. Secondly, legumes are a known host of Sclerotinia – potentially hosting the Sclerotinia during the growth of the cover crop.

The reduction in biofumigant biomass, together with the legume hosting Sclerotinia, resulted in the lettuce crop suffering serious losses under ideal conditions for the disease. A better option would have been to keep with the straight biofumigant and perhaps rotate through a straight cereal in alternative years to add some diversity to the rotation.

Multi-species cover crop – tillage radish & ryegrass cover crop before a processing tomato crop in Shepparton, Victoria. Image courtesy of Kelvin Montagu.

Find out more

Please visit the Soil Wealth website.

For further information, please contact Dr Kelvin Montagu from Applied Horticultural Research at kelvin.montagu@gmail.com.

Soil wealth and integrated crop protection – phase 2 is a strategic levy investment under the Hort Innovation Vegetable, Potato – Processing and Potato – Fresh Funds.

This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable and potato research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: VG16078

Cover image: Multi-species cover crop – oats, tillage radish, field peas & red clover before a potato crop in Manjimup, Western Australia. Image courtesy of Andrew Falcinella.