Liriomyza flies in-focus: Have you seen an exotic leafminer?

Exotic leafminers have been the centre of our attention recently – and with good reason. There are three Liriomyza leafminer species that are now present in Australia: Vegetable leafminer, serpentine leafminer and most recently, American serpentine leafminer. AUSVEG Biosecurity Officer Zali Mahony reports.

Leafminers are small flies that belong to the family Agromyzidae, and concerningly, each species has a wide host range including many vegetable, ornamental and legume crops. Yield losses vary but leaf damage can reduce photosynthetic activity, causing premature leaf drop. These pests are a major threat to Australia’s vegetable industry.

Current situation in Australia

There are three exotic Liriomyza leafminers now present in Australia – vegetable leafminer (VLM; Liriomyza sativae), serpentine leafminer (SLM; Liriomyza huidobrensis) and the most recently detected American serpentine leafminer (ASLM; Liriomyza trifolii).

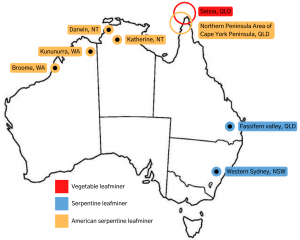

VLM was first detected in 2008 in the Torres Strait Islands and in 2015 at the tip of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland. No further detections have been made.

SLM was first detected in western Sydney, New South Wales in October 2020 and a month later in Queensland’s Fassifern Valley. The pest is now considered established in both states.

Most recently, ASLM was detected in July 2021 in the Torres Strait Islands and across northern Western Australia. There have since been further detections in Kununurra (WA), Darwin and Katherine in the Northern Territory, and the Northern Peninsula Area of Cape York (QLD). There has been a single detection in Broome (WA).

Containment versus management strategy

All three species are considered National Priority Plant Pests. With each pest detection, the Consultative Committee on Emergency Plant Pests (CCEPP) – Australia’s key technical body for coordinating national responses to emergency plant pest incursions – is responsible for determining whether a pest is technically feasible to eradicate.

Following their detection, the CCEPP determined that VLM and ASLM are not technically feasible to eradicate largely due to the pest’s biology, current distribution and wide host range.

A containment strategy is in place for ASLM due to its current distribution limited to some locations in northern Australia. Movement restrictions from the far northern biosecurity zones are in place and have been successful in previously preventing further spread of VLM. For ASLM, delimiting surveillance is still being conducted to determine any potential further distribution of this pest.

SLM was also determined not technically feasible to eradicate due to the extent of the pest’s infestation across NSW and QLD, its biology and wide host range. As a containment strategy was not feasible, a transition to management by industry began in late 2020.

Lifecycle and damage

The lifecycle for Liriomyza leafminers is generally consistent across species. Adults feed on leaves and females lay eggs just below the leaf surface of host plants. This causes ‘stippling’ damage that can be visible in some instances and can cause a high risk of fungal and bacterial infection for the plant.

Eggs hatch between 2-5 days after being laid. Eggs are too small to be seen by the naked eye, so a seemingly healthy plant may be harbouring the pest without us knowing. Inside the leaf tissue, larvae begin to feed within the leaf creating tunnels or mines that become larger as the larvae matures. These leaf mines can reduce photosynthetic activity, causing premature leaf drop.

Larvae then exit the leaf to transition to adults (pupate) externally to the leaf, usually in soil below the plant from which adults emerge 7-14 days later. Other species of Liriomyza leafminers can transition to adults within the leaf tissue, but this is not the case for VLM, SLM or ASLM.

The duration of Liriomyza spp. lifecycles does vary with temperature. Favourable environmental conditions can reduce the time it takes for an entire lifecycle, meaning several generations can occur in one season. In unfavourable environmental conditions, the cycle takes longer.

Identification

Adult Liriomyza species of leafminers are difficult to identify in the field, and molecular diagnostic tests are necessary to confirm species. Exotic species also look similar to native leafminers that are prevalent in Australia (e.g., Liriomyza brassicae). Stippling and leaf mine damage do not differ between Liriomyza species, so cannot be used to separate species. Stippling and leaf mines are the key indicator to look for when monitoring crops and surrounding vegetation.

Risk of spread and establishment

Major risk pathways of leafminers into and across Australia is by the importation of infested ornamental host plants and cut flowers. Leafy vegetables and seedlings can move leafminers across Australia. Natural pathways (such as wind) or human-assisted entry can also occur at the borders (e.g., on plant material illegally imported).

Globally, Liriomyza leafminer dispersal and establishment has rapidly occurred, with populations found on most continents now. Many important vegetable production regions in Australia have the climatic conditions suited to Liriomyza spp. establishment.

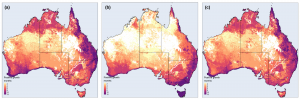

Climate models and existing pest knowledge have been used to determine the pest’s risk of establishment in regions across Australia. A predictive model based on temperature, moisture constraints and predicted dominant stressors (cold, heat, desiccation) was created by Cesar Australia as part the strategic levy investment RD&E program for control, eradication and preparedness for vegetable leafminer (MT16004), which developed a contingency plan for each pest (see further reading section below).

VLM and ASLM are suited to similar climatic conditions and are predicted to likely establish along the northern, eastern, southern and southwestern coastline of Australia and Tasmania (see map images a and c). Both are heat tolerant species, meaning they will thrive in tropical conditions.

However, they are not only tropical pests and are also suited to temperate regions. VLM and ASLM are not as suited to cool-climate regions as other species, but they are still predicted to be able to maintain populations year-round across Australia. ASLM has been reported to have delays in development (diapause) at low temperatures, which will allow them to survive cold conditions, until warmer weather arrives.

Comparatively, SLM adults are reported to be more resilient and able to survive winter temperatures (as low as -11.5oC), with pupae able to survive and transition to adults in temperatures between 5.7oC to 30oC. SLM is most likely to establish along the eastern, southern and south-western coastline of Australia and Tasmania (see map image b).

Pest management

International management of Liriomyza leafminers includes the use of natural enemies such as parasitoid wasps that attack larvae. Research has indicated that exotic Liriomyza leafminers are rapidly targeted by Agromyzid parasitoids, and many are reported to affect these pests overseas. This is promising for future management as these parasitoids tend not to be host-specific, and Australia has several native species that are likely to affect these leafminer pests. There is also initial evidence of the presence of native predators in the Australian environment.

Pest management practices should be mindful of preserving natural enemies and consider the use of pesticides that don’t harm these beneficial insects.

Chemical control options

Liriomyza leafminers can rapidly develop resistance to various chemical groups – particularly organophosphates, carbamates, diamides and pyrethroids – which can make control difficult.

Application of broad-spectrum insecticides often results in larger leafminer populations as these insecticides reduce the reservoir of natural enemies (parasitoid wasps as well as other generalist predators like spiders), which keep leafminer populations in check. Translaminar and systemic chemical options support better support the management of leafminers as they are not harmful to the natural enemies.

Several insecticides are used overseas for the control of exotic leafminers, including – but not limited to – abamectin, azadirachtin, chlorantraniliprole, cyromyzine, indoxacarb, spinetoram and spinosad.

There are several minor use permits currently available for Liriomyza leafminers for the vegetable and potato industry. For more information, please visit horticulture.com.au/growers/serpentine-leafminer-update.

Further reading

- Management of leafmining flies in vegetable and nursery crops in Australia: ly/2X1vkps

- Monitoring for serpentine leafminer in Australia: ly/3D21UqC

- AUSVEG biosecurity alerts: ly/3hjOjTo

- Plant Health Australia – Liriomyza fact sheets, diagnostic protocols and contingency plans:

- Vegetable leafminer: ly/3tuLDau

- Serpentine leafminer: ly/2X59Rfj

- American serpentine leafminer: ly/38P6gEE

Leafminer snapshot

- Adult flies are between 1-1.7 mm.

- Adults are a mixture of black and yellow which differs for each species.

- Larvae are initially transparent transiting to yellow-orange as they mature.

Find out more

Please contact the AUSVEG Extension & Engagement Team on 03 9882 0277 or email science@ausveg.com.au.