Exploring the internal issues affecting capsicums

Internal fruit rot can be a significant issue for capsicum growers. In response to this, a project is aiming to deliver capsicum growers with an integrated disease management strategy to control internal rot, as well as developing a predictive model that will help growers identify crops at risk and diagnose infection early. Dr Jenny Ekman from Applied Horticultural Research reports.

Picture the scene: a suburban kitchen, preparing the dinner after a long day at work. It might be a stir fry, or pasta, but with one vital ingredient – red capsicum. But cutting open the apparently perfect, glossy fruit reveals a ball of revolting grey fluff. Yuck!

The supply chain includes many checks to intercept rotten products before they get to market. There’s the picker, the sorter, the box filler and finally quality control (QC) and retail staff. But how to find a problem that’s inside the product – invisible, until cut open?

Internal mould in capsicums is a sporadic issue affecting many, if not all, capsicum and chilli producing regions. Warm temperatures and high humidity favour the disease. Although infection is widely believed to occur at flowering, symptoms do not usually develop until the capsicum starts to ripen, spreading most rapidly after harvest. The fungus is usually found growing over the seeds but can also develop from the flower end of the fruit.

There are several different fungi that may cause internal rot. In the northern hemisphere, Fusarium spp. has been identified as the fungi responsible. However, samples collected some years ago in Bundaberg were found to be infected by Alternaria spp. As control strategies differ between fungal species, identifying the causal organism is an important first step for managing the disease.

Getting inside information

Applied Horticultural Research is investigating internal rot of capsicums. A strategic levy investment under the Hort Innovation Vegetable Fund, Internal fruit rot of capsicum (VG17012) aims to identify the fungus/fungi causing this problem as well as develop management techniques to prevent infection, reduce postharvest development and minimise the risk of sending unacceptable fruit to market.

In February this year, the project team collected a number of samples of flowers and fruit from both capsicums and chillies in southern Queensland. Isolates of Alternaria were recovered from flowers, discoloured seeds and the dried remains of the style (the small, black fragment which sticks to the base of the fruit). Alternaria was also recovered from fruit with symptoms of black mould – an external infection resulting from blossom end rot or sunscald.

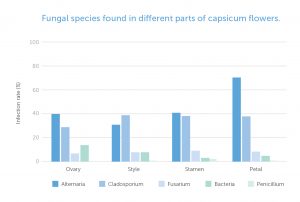

Whereas internal rot was a relatively minor issue for Queensland growers coming out of drought, sampling in the Sydney Basin during March revealed a bigger issue. On average, 29 per cent of capsicums had symptoms of internal rot. Species of Alternaria, Cladosporium, Fusarium and Penicillium fungi, as well as a few bacteria, were all isolated from various flower parts. While Alternaria was isolated most frequently from the petals, the carpel (ovary, stigma and style) and stamens were also commonly infected with different fungi. This suggests that a there are a range of pathogens present at flowering, which could potentially transfer into the developing fruitlet.

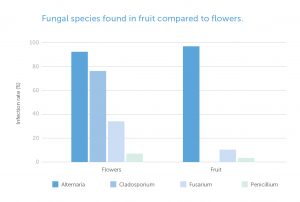

In contrast, Alternaria was overwhelmingly the main pathogen isolated from fruit. In total, Alternaria spp. was isolated from 92 per cent of flowers and 97 per cent of fruit with internal rot symptoms. Interestingly, at least three different ‘small spored’ types of Alternaria were present. This group includes A. alternata, but also A. arborescens and A. tenuissima. Identifying to species and strain can only be done through molecular methods – an important next step with these isolates.

Identification of the fungi responsible for internal rot has been further confounded by flower samples received from Bundaberg. Local collaborators collected multiple replicates of capsicum flowers from crops in Calavos, Alloway, Moorelands and Meadowvale for analysis at Applied Horticultural Research’s Sydney laboratory. From a total of 400 flowers, not one was found to have Alternaria spp.. Instead, incubation revealed that many were infected with various species of Fusarium.

At the time the flowers were sampled, there were no mature fruit on the plants. However, as the capsicums develop and ripen over the next few weeks, we hope to discover whether or not Fusarium-infected flowers cause fruit with internal mould.

Flowers isolated for incubation, allowing any fungi present to develop. Images courtesy of Applied Horticultural Research.

Further research

Meanwhile, Honours student Ryan Hall is growing three commercial varieties of capsicum in the Sydney University glasshouse. The flowers will be tagged and artificially inoculated with different strains of Alternaria and potentially Fusarium. When the resulting fruit mature, they will be examined at for symptoms of internal rot. We hope that this will establish whether the infection that causes internal mould really does occur during flowering, and if more than one type of fungi can be responsible.

It is early days for the project, and we are keen to get more samples of capsicums with internal mould. Ideally, we would like a number of samples from each capsicum producing region – that way we can gain an overview of fungi responsible.

If you or someone you know does have that experience of finding a ball of grey fluff inside an otherwise beautiful red, yellow or even green capsicum, then please contact the project team.

Find out more

For more information, or to send samples, please contact Dr Jenny Ekman from Applied Horticultural Research at jenny.ekman@ahr.com.au.

This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable research and development levy and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: VG17012

This article first appeared in the winter 2020 edition of Vegetables Australia. Click here to read the full publication.