Special investigation: What’s this grey fluff inside my capsicum?

Since late 2019, a project has been investigating the causes behind internal fruit rot in capsicums, as well as developing management techniques for growers to prevent infection and minimise the risk of sending damaged fruit to market. Project Lead Dr Jenny Ekman from Applied Horticultural Research reports on the latest findings.

Internal mould of capsicums is a major issue in many growing regions. While external rots are bad enough, trying to detect and control a fungus that only appears once the fruit matures and is invisible from the outside – that’s a challenge.

Yet, this is what is expected by the capsicum-consuming public, who can be quick to complain on discovering a ball of fluff inside an otherwise apparently perfect red fruit. The result is that retailers have minimal tolerance for internal mould, a requirement enforced by cutting samples of fruit on receival.

A strategic levy investment under the Hort Innovation Vegetable Fund, Internal fruit rot of capsicum (VG17012) has been examining the causes of internal mould and trying to develop management strategies for this disease.

The organism responsible

While it is generally thought that infection occurs during flowering, it has been unclear as to which organism is responsible.

Therefore, the first step of the project was to identify the cause of disease and confirm whether infection did indeed occur at flowering.

“We isolated a number of different fungi from infected capsicums sourced in Sydney Basin as well as sent from Bundaberg and Bowen. These included Alternaria, Fusarium, Penicillium and Cladosporium,” plant pathologist and project team member, Dr Len Tesoriero, said.

“While Alternaria spp. was the most common, at least two different species were present. There were also several species of Fusarium, with visibly different symptoms between fruit.”

To test whether these fungi could cause the observed symptoms, University of Sydney Honours student Ryan Hall conducted greenhouse trials inoculating spores onto the flowers of four different capsicum varieties, then re-isolating fungus from any infected fruit that developed.

Two Alternaria and one Fusarium were confirmed as causing internal mould. Ryan then used molecular techniques to identify the isolates to species. This revealed the three fungi to be Alternaria tenuissima, Alternaria alternata and Fusarium oxysporum. All three are common in the growing environment and can cause disease in a large range of plant hosts.

Fusarium lactis, which is the main cause of internal mould in greenhouse crops in the northern hemisphere, was not found. It is also interesting to note that infection rates under the ‘ideal’ conditions in the greenhouse ranged from 8 to 17 per cent, which is lower than has been observed under field conditions.

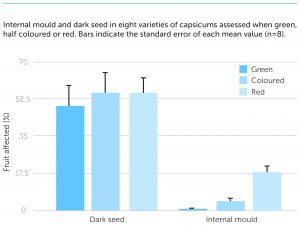

Myth busted: Dark seed does not turn into mould

As well as internal mould, capsicums can develop a condition known as ‘dark seed’. On occasion, capsicums with dark seed have been classed as mouldy by Quality Assurance staff, leading to product rejections. However, while this condition may look like the start of disease, there is now good evidence this is not the case.

“We plated out more than 50 samples of dark seeds onto agar plates to see what would develop,” Dr Tesoriero said.

“The answer was nothing. Instead, this is most likely a physiological issue. There is certainly no evidence dark seed can turn into internal mould.”

Variety trials

While internal mould is a curse in many production regions, it is rarely found in South Australia. This could be due to fruit being produced undercover, a generally dry climate or differences in varieties grown – Adelaide growers favour the longer, more pointed varieties than the blocky types grown in other districts.

“Assessments of capsicums from Bowen and Bundaberg suggested that new varieties might be less susceptible to the disease,” Project Lead Dr Jenny Ekman explained.

“We wanted to set up trials in Queensland, but COVID-19 restrictions meant we couldn’t travel. Fortunately, staff from Bayer-Seminis were able to step into the breach. They set up two trials involving a total of 11 varieties near Stanthorpe, Queensland, which was incredibly helpful.”

“We also planted our own trial with six varieties in Richmond, New South Wales. These included new varieties as well as traditional blocky types favoured by local growers and a couple of the ‘half longs’, commonly grown under protected cropping.”

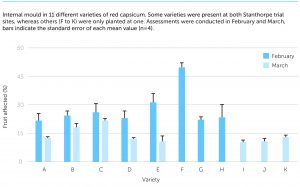

The two sites near Stanthorpe were assessed in February and March 2021.

At least 100 fruits and varieties were cut and examined for signs of internal mould.

“Unfortunately, there were no clear differences between old and new varieties, or between blocky and half-longs,” Dr Ekman said.

“However, it was clear that rates of internal mould were much higher in February than in March. While symptoms were often very slight, a massive 28 per cent of red fruit had signs of internal mould in February! This halved to a still significant 14 per cent of fruit affected in March. This may reflect weather conditions at flowering – something we really need to look into closely.”

It was also clear that internal mould only becomes a problem as fruit ripen to full red colour.

“Picking fruit while half red or chocolate greatly reduced the likelihood that it would contain internal mould, while the disease was almost never found in green fruit,” Dr Ekman said.

“In contrast, dark seed does not change significantly as fruit mature. This seems to further confirm that this condition is entirely separate to internal mould.”

At the Richmond trial site, red fruit was ready to pick during March.

“We were all set to assess the varieties and had started a second trial examining combinations of various fungicides. That’s when the rain started,” Dr Ekman explained.

“The rest is history – the water came up and the capsicums went out to sea, leaving us with nothing but some muddy stumps. We are keen to replant but it’s getting too cool, so will have to wait until next summer.”

Red capsicums look and taste great, so can attract premium prices. However, leaving the fruit on the plant for longer certainly adds risk. Understanding when risk is higher, and so being able to decide which crops to pick green and which to leave as reds, will form the next stage of the project.

Find out more

For more information, please contact Dr Jenny Ekman from Applied Horticultural Research at jenny.ekman@ahr.com.au.

This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable research and development levy and contributions from the Australian Government.

Project Number: VG17012